I’ve never met Gord Downie. Never even been to a Tragically Hip concert. But watching Gord weave his magic at the band’s last concert in August–where, by some alchemy of love and creative energy, he gave it more than he had–made me want to give him something in return.

As a writer all I have is words, but words have power. When I taught school, the best gift I ever received was a thank you note. So to Gord Downie, who has been a teacher to thousands without ever stepping into a classroom, I want to say, “Thanks for making me a better writer.”

Because besides being a courageous soul who sings his heart out, Gord Downie is a gifted writer. His lyrics resonate with that giant ball of hopes and dreams and fears we call the human condition.

Take the song “Bobcaygeon” for instance. Gord manages to create a short story in four simple verses. Brilliant. We should all take notes. Here are six key lessons I learned:

1. Start in the middle of things. The song opens with a man leaving someone’s house. Whose house? He doesn’t say. Why is the time important? We don’t know. Hmmm, a mystery. He feels guilty about something, though, because he starts making excuses: “Could have been the Willie Nelson, Could have been the wine.”

2. Introduce the Main Character, but only Key Details. We know what our protagonist listens to, what he drinks, and his habit of making excuses. (That’s more important than what he looks like, in my opinion.) Notice there’s no backstory, just action and inner dialogue. That’s how it should be.

3. Show don’t tell, especially when it comes to emotion. The first verse ends with this gem: “I saw the constellations reveal themselves one star at a time.” Ah. We’ve all read enough Shakespeare to know that a man staring at the stars is in love. Note that love isn’t mentioned. Love is abstract–talking about abstract concepts doesn’t make us feel anything. The image of a man staring at the stars does.

4. Don’t stop the action to create setting and mood. In the next verse the mood changes. No more stargazing, no more Bobcaygeon–our main character goes back to bed, pulling down the blind on a sky that’s “dull, and hypothetical and falling one cloud at a time.” Talk about a downer. Once again, there is no direct mention of emotion. Instead we sense the mood through his simple act of pulling down the blind.

5. Don’t get bogged down with description. When it comes to description my motto is “Leave out the boring bits.” Gord has that down to a fine art. In verse three we find ourselves in Toronto. Our main character is riding horseback, keeping order during a demonstration. Or maybe a riot. Clearly he’s a policeman. A picture forms in our heads–no description necessary. There’s a confusing mix of images–a checkboard floor, a mic, Aryan voices. It’s a jumbled mess, which is exactly what a riot would be.

6. Have the ending reflect the beginning, but with a change. In the last verse we’re back in Bobcaygeon. Same time, same place–with a change. Our main character owns his feelings now: “Couldn’t get you off my mind.” He’s braver, bolder, no excuses. Once again, Gord doesn’t tell us this; he shows us through his character’s actions. Why does he remind us of the constellations at the end? Perhaps to reinforce the setting and the emotion. After all, this is a love song. Or perhaps to leave us with one iconic Canadian image–the northern sky at night.

Gord Downie was once quoted as saying “A great song’s greatest attribute is how it hints at more.” Do the same with your writing.

the buffalo his family needs in order to survive the coming winter. This deceptively simple prose is rich with lessons on both native life and story structure. The vivid artwork illustrates many aspects of Cree culture. Though not about residential schools, I had to include it because of the brilliant artwork and the story it tells of a tradition that is dying because of colonization. Wiebe is an award-winning Alberta writer. Michael Lonechild is a celebrated artist from White Bear Reserve, Saskatchewan.

the buffalo his family needs in order to survive the coming winter. This deceptively simple prose is rich with lessons on both native life and story structure. The vivid artwork illustrates many aspects of Cree culture. Though not about residential schools, I had to include it because of the brilliant artwork and the story it tells of a tradition that is dying because of colonization. Wiebe is an award-winning Alberta writer. Michael Lonechild is a celebrated artist from White Bear Reserve, Saskatchewan. wolves from the land. When Red Wolf, a young Anishnaabek boy, finds Crooked Ear, an orphaned wolf, he wants to adopt it. But his father says no. Under the Indian Act, Red Wolf must go to a residential school and his family must live on a reservation far away. The story alternates between the POV of the wolf and the boy, giving it an added appeal. But this isn’t a feel-good story about a boy and his pet. It refuses to minimize the violence of the residential school experience, and the opening scene portrays an act of cruelty that will make you squirm. Teachers will want to address these issues before students read this novel.

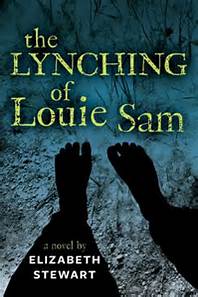

wolves from the land. When Red Wolf, a young Anishnaabek boy, finds Crooked Ear, an orphaned wolf, he wants to adopt it. But his father says no. Under the Indian Act, Red Wolf must go to a residential school and his family must live on a reservation far away. The story alternates between the POV of the wolf and the boy, giving it an added appeal. But this isn’t a feel-good story about a boy and his pet. It refuses to minimize the violence of the residential school experience, and the opening scene portrays an act of cruelty that will make you squirm. Teachers will want to address these issues before students read this novel. When fifteen-year-old George Gillies finds the body of a murdered man in a cabin in Noosack Valley, Washington Territory, rumours begin to swirl. Soon the uneasy relations between settlers and Native people are enflamed. Caught in the frenzy, George and his friend Pete follow the lynch mob north into Canada, on the trail of Louie Sam, a 14-year-old Sto:lo boy suspected of the murder. Told from the point of view of George, we feel his shock as he witnesses an act of unspeakable violence and injustice. Though George Gillies and his family are fictional, this novel is based on the true story of Louie Sam. Depicting the brutality of racism and the dangers of mob rule, it makes a good vehicle for discussion on how to stand up for what you believe, even when it means losing your friends.

When fifteen-year-old George Gillies finds the body of a murdered man in a cabin in Noosack Valley, Washington Territory, rumours begin to swirl. Soon the uneasy relations between settlers and Native people are enflamed. Caught in the frenzy, George and his friend Pete follow the lynch mob north into Canada, on the trail of Louie Sam, a 14-year-old Sto:lo boy suspected of the murder. Told from the point of view of George, we feel his shock as he witnesses an act of unspeakable violence and injustice. Though George Gillies and his family are fictional, this novel is based on the true story of Louie Sam. Depicting the brutality of racism and the dangers of mob rule, it makes a good vehicle for discussion on how to stand up for what you believe, even when it means losing your friends. If my cats, Jack and Suzy, wrote a book, it would be a bestseller. They have an intuitive understanding of plot (cat wants food and will do anything to get it) a therapist’s grasp of character (how to wake sleeping humans at 5 am) and a willingness to explore any setting (how did they get in there?)

If my cats, Jack and Suzy, wrote a book, it would be a bestseller. They have an intuitive understanding of plot (cat wants food and will do anything to get it) a therapist’s grasp of character (how to wake sleeping humans at 5 am) and a willingness to explore any setting (how did they get in there?)